Why Gabon’s coup leader is bucking a trend by embracing democracy

Written by BBC on April 10, 2025

Little more than 19 months after the bloodless coup that brought an end to more than five decades of rule by the Bongo family, the people of Gabon are about to head to the polls to choose a new head of state – bucking a trend that has seen military leaders elsewhere in Africa cling on to power.

The overwhelming favourite in the race on Saturday is the man who led that peaceful putsch and has dominated the political scene ever since, Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema.

Having abandoned his soldier’s fatigues and military status in favour of a politician’s suit, this highly articulate former commander of the elite Republican Guard faces seven other candidates.

Basking in popularity among a population relieved to be rid of dynastic rule – and assisted by electoral regulations that disqualified some key challengers – the 50-year-old appears almost certain to secure an outright majority in the first ballot.

His campaign slogan – using his initials “C’BON” – is a play on the French words “c’est bon”, meaning “it’s good”.

Alain-Claude Bilie-By-Nze, the last prime minister under ousted President Ali Bongo, is the coup leader’s main rival

Reuters

His chances of avoiding a second round run-off are bolstered by the fact that his main challenger – one of the rare senior political or civil society figures not to have rallied to his cause – is the old regime’s last prime minister, Alain-Claude Bilie-By-Nze, known by his initials ACBBN.

Victory will bring a seven-year mandate and the resources to implement development and modernising reform at a pace that the rulers of crisis-beset African countries could not even dream of.

With only 2.5 million people, Gabon is an established oil producer and the world’s second-largest exporter of manganese.

Its territory, which sits astride the equator, encompasses some of the most biodiverse tracts of the Congo Basin rainforest.

And other than a harsh post-election crackdown in the capital, Libreville, in 2016, the country has enjoyed a mostly calm recent history that contrasts with the conflicts and instability that have afflicted many regional neighbours.

Oligui Nguema and his Republican Guards met no resistance when they seized power on 30 August 2023, just hours after the electoral authorities had taken to the airwaves in the middle of the night to proclaim that the incumbent President, Ali Bongo Ondimba, had secured a third seven-year term with a crushing 64% of the vote.

It was hard to see this official result as credible. Ali Bongo, who succeeded his father Omar in 2009, had only squeaked a narrow and much disputed victory in the previous poll, in 2016.

When he suffered a stroke while visiting Saudi Arabia two years later and embarked on a painstaking gradual recovery there had been widespread popular sympathy.

But the mood shifted after he decided to stand for a third term, despite his visibly frail state of health – this fuelled widespread resentment at the supposed behind-the-throne influence and ambitions of his French-born wife Sylvia and his son Nourredin Bongo Valentin.

The military’s peaceful intervention to forestall a continuation of the regime, arresting Sylvia and Nourredin and confining Ali in enforced retirement in his private villa, triggered spontaneous celebrations among the many Gabonese who had grown weary of this apparently immovable dynasty.

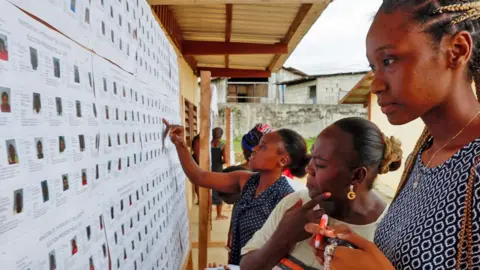

Voters in the oil-rich nation, where more than a third of the population lives in poverty, will get to choose from eight presidential candidates

Reuters

And the coup was greeted with relief even by most of the administrative, political and civil society elite.

Oligui Nguema took shrewd advantage, reaching out to build a broad base of support for his transitional regime. He brought former government figures, opponents and prominent hitherto critical civil society voices into the power structure or institutions such as the appointed senate.

Political detainees were freed, though Ali Bongo’s wife and son remain in detention awaiting trial on corruption charges.

He did not resort to the sort of crackdowns on dissent or media freedom that have become a routine tool of Francophone Africa’s other military leaders, in Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Niger.

Oligui Nguema, unlike military leaders in West Africa, has maintained cordial relations with France and President Macron

AFP

On the diplomatic front, in marked contrast to the assertively anti-Western posture adopted by the regimes in West Africa, Oligui Nguema despatched senior figures to cultivate international goodwill and reassure Gabon’s traditional partners of his determination to restore civilian constitutional government within a tightly limited timeframe.

Relations with France, the former colonial power and previously a close ally of the Bongo regime, are warm.

The two governments recently agreed to transform Camp de Gaulle, the longstanding French base in Gabon, into a new training centre that they will operate jointly.

Displaying a deft popular and political touch, Oligui Nguema has responded to public hunger for change with an acceleration of public works and delayed projects.

And at a time of rising popular support across Francophone Africa for a more visibly assertive defence of national interests, his government has acquired the Gabonese assets of several foreign oil companies, including the UK’s Tullow.

An ambitious plan was launched last year to upgrade Gabon’s only railway, which is built through dense equatorial forest

AFP

Much of the $520m (£461m) raised through a Eurobond in February has been used to pay off old debt, and the government has also set aside funds to clear some arrears owed to the World Bank.

But if, and almost certainly when, he is elected as Gabon’s head of state on Saturday, Oligui Nguema will face significant challenges.

Such was the public’s hunger for change that, in many ways, the transition has been the easy part. There has been little public pressure constraining his freedom of manoeuvre.

There was broad consensus over incorporating a ban on dynastic succession in the new constitution.

When Oligui Nguema brushed off some parliamentarians’ concern about the concentration of executive power in the presidency by abolishing the post of prime minister, there was little fuss.

But this does mean that, going forward, the full weight of responsibility for meeting public expectations will fall on his shoulders alone.

Prominent political and civil society figures, such as veteran opponent Alexandre Barro-Chambrier and rainforest campaigner Marc Ona Essangui, have joined his transitional administration or political machine, the Rassemblement des Bâtisseurs (RDB), and could well occupy important roles post-election.

Nonetheless the focus will be on Oligui Nguema himself. And he will face complex challenges.

Nearly 90% of Gabon is covered by forest and the Ogooué River, pictured here near the inland city of Lambaréné, flows through the middle

Reuters

Gabon has long positioned itself as a leader in conserving the rainforest and its enormously diverse flora and fauna, attracting international praise for its astute use of climate finance tools – in 2023 it became the first sub-Saharan country to complete a debt-for-nature swap.

But this strategic approach has to be reconciled with the economic pressure to make full use of other natural resources, particularly minerals and oil, and with the needs of rural communities seeking to protect their hunting and farming rights.

Urban populations, particularly in Libreville – home to almost half the country’s population – need more jobs and better services, in a country whose social development record has been disappointing, given its relative affluence.

Trade unionist Jean Rémy Yama, excluded from the presidential race because he could not produce his father’s birth certificate, a nomination requirement, is one figure with a considerable following who could give voice to popular frustrations.

For Oligui Nguema, the hardest work is about to begin.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.