‘Once-in-a-century’ discovery reveals spectacular luxury of Pompeii

Written by BBC on January 17, 2025

After lying hidden beneath metres of volcanic rock and ash for 2,000 years, a “once-in-a-century” find has been unearthed in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii.

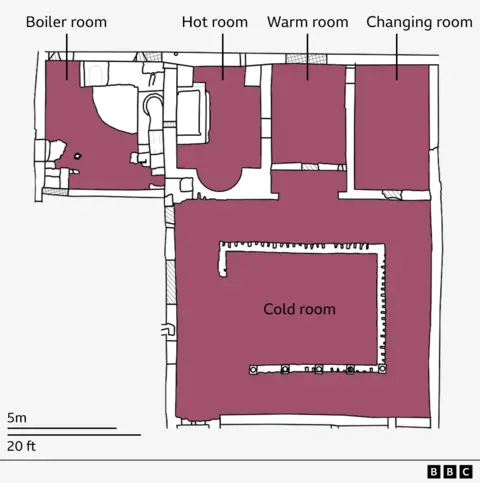

Archaeologists have discovered a sumptuous private bathhouse – potentially the largest ever found there – complete with hot, warm and cold rooms, exquisite artwork, and a huge plunge pool.

The spa-like complex sits at the heart of a grand residence uncovered over the last two years during a major excavation.

“It’s these spaces that really are part of the ‘Pompeii effect’ – it’s almost as if the people had only left a minute ago,” says Dr Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, who has revealed the new find exclusively to BBC News.

The bathhouse changing room has vibrant red walls, a mosaic floor and stone benches

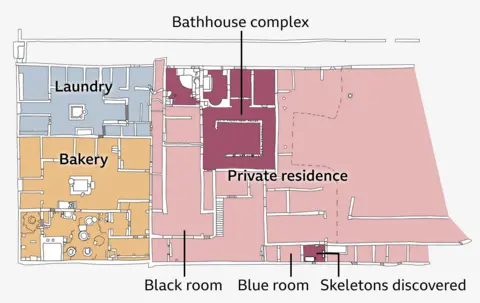

Analysis of two skeletons discovered in the house also shows the horror faced by Pompeii’s inhabitants when Mount Vesuvius erupted in AD79.

The bodies belonged to a woman, aged between 35 and 50, who was clutching jewellery and coins, and a younger man in his teens or early 20s.

They had barricaded themselves into a small room, but were killed as a tsunami of superheated volcanic gas and ash – known as a pyroclastic flow – ripped through the town.

“This is a dramatic place, and everything you find here tells you about the drama,” says Pompeii conservator, Dr Ludovica Alesse.

A third of the ancient city still lies hidden beneath volcanic debris from the disaster, but the new excavation – the most extensive in a generation – provides new insights into ancient Roman life.

The archaeologists have been followed by a documentary team from the BBC and Lion TV, for a series called Pompeii: The New Dig.

An entire block of Pompeii has now been uncovered, revealing a laundry and bakery, as well as the large private house. It’s thought these were all owned by one wealthy individual, possibly Aulus Rustius Verus, an influential Pompeii politician.

The discovery of the bathhouse is further confirmation of his elite status, says Dr Zuchtriegel.

“There are just a few houses that have a private bath complex, so it was something really for the wealthiest of the wealthy,” he says. “And this is so huge – it’s probably the biggest bath complex in a Pompeiian private home.”

Twenty to 30 people could bathe in the cold room’s plunge pool, which is more than 1m deep

Those lucky enough to use the suite of bathing rooms would have undressed in a changing room with vibrant red walls and a mosaic floor dotted with geometric patterns inlaid with marble from across the Roman Empire.

They would then head to the hot room, taking a dip in a bath and enjoying the sauna-like warmth, provided by a suspended floor that allowed hot air to flow underneath and walls with a cavity where the heat could circulate.

Next they would move to the brightly-painted warm room, where oil would be rubbed into the skin, before being scraped off with a curved instrument called a strigil.

Finally, they would enter the largest and most spectacular room of all – the frigidarium, or cold room. Surrounded by red columns and frescoes of athletes, a visitor could cool off in the plunge pool, which is so large 20-30 people could fit in it.

“In the hot summers, you could sit with your feet in the water, chatting with your friends, maybe enjoying a cup of wine,” says Dr Zuchtriegel.

The bathhouse is the latest find to emerge from this extraordinary house.

A huge banqueting room with jet black walls and breathtaking artwork of classical scenes was found last year. A smaller, more intimate room – painted in pale blue – where residents of the house would go and pray to the gods was also unearthed.

The residence was mid-renovation – tools and building materials have been found throughout. In the blue room a pile of oyster shells lie on the floor, ready to be ground up and applied to the walls to give them an iridescent shimmer.

A small blue room used for prayer. Amphoras – terracotta containers used to transport olive oil or wine – are resting against a wall. Oyster shells are piled on the floor

Next door to this beautiful space, in a cramped room with barely any decoration, a stark discovery was made – the remains of two Pompeiians who failed to escape from the eruption.

The skeleton of a woman was found lying on top of a bed, curled up in a foetal position. The body of a man was in the corner of this small room.

“The pyroclastic flow from Vesuvius came along the street just outside this room, and caused a wall to collapse, and that had basically crushed him to death,” explains Dr Sophie Hay, an archaeologist at Pompeii.

“The woman was still alive while he was dying – imagine the trauma – and then this room filled with the rest of the pyroclastic flow, and that’s how she died.”

Analysis of the male skeleton showed that despite his young age, his bones had signs of wear and tear, suggesting he was of lower status, possibly even a slave.

The woman was older, but her bones and teeth were in good condition.

The skeleton of a woman, clutching coins, was found curled in a foetal position

“She was probably someone higher up in society,” says Dr Hay. “She could have been the wife of the owner of the house – or maybe an assistant looking after the wife, we just don’t know.”

An assortment of items were found on a marble table top in the room – glassware, bronze jugs and pottery – perhaps brought into the room where the pair had tucked themselves away hoping to wait out the eruption.

But it’s the items clutched by the victims that are of particular interest. The younger man held some keys, while the older woman was found with gold and silver coins and jewellery.

A pair of gold and natural pearl earrings found close to the female skeleton

These are kept in Pompeii’s vault, along with the city’s other priceless finds, and we were given a chance to see them with archaeologist, Dr Alessandro Russo.

The gold coins still gleam as if they were new, and he shows us delicate gold and natural pearl earrings, necklace pendants and intricately etched semi-precious stones.

“When we find this kind of object, the distance from ancient times and modern times disappears,” Dr Russo says, “and we can touch a small piece of the life of these people who died in the eruption.”

Archaeologist Alessandro Russo holds a gold coin found with the female skeleton

Dr Sophie Hay describes the private bathhouse complex as a once-in-a-century discovery, which also sheds more light on a darker side of Roman life.

Just behind the hot room is a boiler room. A pipe brought water in from the street – with some syphoned off into the cold plunge pool – and the rest was heated in a lead boiler destined for the hot room. The valves that regulated the flow look so modern it’s as if you could turn them on and off even today.

With a furnace sitting beneath, the conditions in this room would have been unbearably hot for the slaves who had to keep the whole system going.

Archaeologist Alessandro Russo holds a gold coin found with the female skeleto

“The most powerful thing from these excavations is that stark contrast between the lives of the slaves and the very, very rich. And here we see it,” says Dr Sophie Hay.

“The difference between the sumptuous life of the bathhouse, compared to the furnace room, where the slaves would be feeding the fire toiling all day.

“A wall is all that could divide you between two different worlds.”

The excavation is in its final weeks – but new discoveries continue to emerge from the ash. Limited numbers of visitors are allowed to visit the dig while it’s ongoing, but eventually it will be fully opened to the public.

“Every day here is a surprise,” says Dr Anna Onesti, director of the excavation.

“Sometimes in the morning I come to work thinking that it’s a normal working day – and then I discover we found something exceptional.

“It’s a magic moment for the life of Pompeii, and this excavation work offers us the possibility to share this with the public.”